Medieval monastic centres

as beacons of European culture

The monastic system as it developed in Europe from the 4th century onwards and flourished between the 6th and 13th centuries played a key role in the social and cultural unification of the continent.

The origins of Western monasticism

The earliest experiences of ascetic life practised by Christians, also as a part of a community, occurred in both the East and the West between the 2nd and 3rd centuries but the origins of monasticism are found in the near East, in Egypt, Syria, Palestine, and Asia Minor from the second half of the 3rd century onwards, when the monasteries (or cenobies) in Tabenissi on the banks of the Nile sprang up around the figure of St Pachomius, and in Caesarea in Cappodocia around St Basil. Women too at the same time formed groups of their own in order to live together in silence and prayer.

The origins of Western monasticism date back to the 4th century, when St Athanasius of Alexandria and, later, St Jerome described monastic life as it was being practised in the near East. Initiatives inspired by the ideals of monasticism sprang up and flourished all over Europe – with St Martin of Tours and and St Augustine (4th century), St Germanus of Auxerre in Britain and St Patrick in Ireland (5th century), and the monks of Lérins in Provence (5th century). The 6th century saw a flowering of monasteries in Spain, the British Isles and France.

From the 6th century onwards in Italy new hermitic communities started to emerge, which experimented with a way of living based on prayer, asceticism, charitable works, and on occasion the study of Scripture, experiences which were encouraged and supported by local bishops or, in Rome, by the city’s nobility. In the south of Italy forms of monastic life influenced by Byzantine culture are found. It was in this context that Benedict of Norcia (ca. 480-547) grew up and began his spiritual journey. After spending time as a hermit in a cave near the town of Subiaco, Benedict founded twelve small communities of disciples in the environs of Subiaco. In 529 he settled in Montecassino. Here he established what was to become a formal monastic community and completed the writing of his Rule.

Monastic centres in medieval and modern Europe

The rise of the Benedictine order in Europe

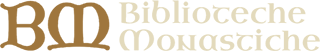

To begin with, the Regula Sancti Benedicti was little known outside the monastic centres and the surrounding areas. In the 6th century, Gregory the Great founded a place of worship and a small community which took its inspiration from the Benedictine Rule; later, during the 8th century, the work also inspired monastic life in France and Ireland. But the real watershed occurred during the Carolingian period (9th century), thanks to the work of Benedict of Aniana which played a crucial role in the spread of the Benedictine order throughout the continent:

…everyone followed a single rule and every monastery practised an identical way of life, so that it seemed as if each monk had been educated by the same master and in the same place…

as it is written in the life of Benedict of Aniana. The Benedictine monasteries thus became the leading “monastic family” in medieval Europe and the spiritual and intellectual activities pursued there contributed to the continent’s expanding potential, its development and its cultural growth.

The feeling that there was a need to return to the strict observance of St Benedict’s Regola and to attempt a renewal of monastic life can be seen as early as 1000. What was in effect a revival and rebirth of Benedictine monasticism was led above all by the Cluniac and Cistercian orders (beginning of 10th century and end of 11th centuries respectively), while new forms of hermitic life, such as the Williamites in the 12th century, and monastic life, such as the Camaldolese (first half of 11th century) and Carthusians (end of 11th century) began to spring up. In Italy Cluniac reforms were introduced in already established monasteries such as the imperial Abbey of Farfa and the Cistercian approach is the Abbey of Casamari. By contrast, the monastery of Trisulti in Collepardo was assigned to the Carthusians. It was only later, in the 13th century, that the mendicant orders arose: the Dominicans or preaching order and the Franciscans.

A new drive to renew Benedictine monasticism can be seen in the late Middle Ages. In the province of Siena, the Benedictine Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore (1313) was founded, the motherhouse of the Olivetan order, while in Padua, the abbot Ludovico Barbo led the reform of the Benedictine Abbey of Santa Giustina (1409), which became a centre for a numerous group of other monasteries, such as the Abbey of Montecassino, the Badia of Cava dei Tirreni and Praglia, to form the Cassinese Congregation.

In the early modern period, during the prolonged crisis of the Reformation culminating in the Counter Reformation, new religious orders sprang up, such as the Jesuits, the Oratorians, the Theatines. In France in 1618 the Benedictines united round the Congregation of St Maur or Maurists. The first scholars to establish the disciplines of diplomatics and palaeography, in the study of medieval documents, Jean Mabillon and Bernard de Montfaucon were Maurists.

Monasteries as creators and communicators of knowledge

Libraries and medieval scriptoria

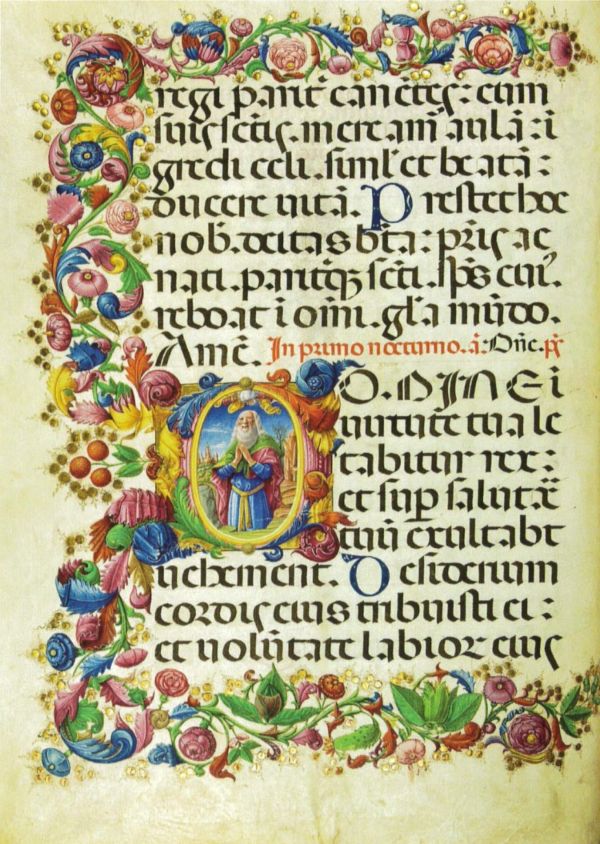

In the Middle Ages, the monastic system –in effect the Benedictine system, which was the most widespread and organised – played a key role in the cultural unification of Europe. Monasteries were centres for the study, production, conservation and transmission of human knowledge while their libraries and the fact that monks travelled between different monasteries across the continent led to what was a fruitful exchange in various fields and disciplines. Benedictine monasteries formed one large cultural network which went beyond political boundaries and united the centres of southern Italy to the monasteries in the valley of the Po and the Alpine regions, Spain and Portugal, and the British Isles. Scholarship, spirituality and art were fused in the manuscripts which were transcribed and decorated by the monks. Thanks to their untiring efforts and their skills Greek and Latin classics have come down to us, together with the writings of the Church Fathers, the Scriptures, liturgical and devotional works, of theology and philosophy, geography and history, and of science (medicine, botany, mathematics, astronomy, etc.) and related fields.

With the advent of the modern age, and just as it had done during the Middle Ages, the monastic world continued to create and diffuse knowledge across Europe. A few years after the invention of printing with mobile types in Germany, the first printing press in Italy (1464-1467) was set up in the Benedictine monastery in Subiaco. Monastic libraries acquired printed books for the purposes of study, of liturgy, and for the education of novices. In all the great centres of printing such as Venice, Augsburg, Erfurt, Nuremberg, Brussels, Cologne, etc., scholarly monks were closely involved in the production of early printed editions, as authors, editors, translators and printers.

In the 17th century, the first scientific investigations of the world of books, manuscripts and archival documents giving rise to the disciplines of palaeography and diplomatics, philology and patristics, also emerged within the European monastic network, thanks to the studies of erudite Maurists such as Jean Mabillon and Bernard de Montfaucon. Between the 16th and the 18th centuries libraries belonging to ecclesiastical institutions (monasteries and convents) amounted to over 25% of all existing libraries; together with the libraries belonging to cardinals, the higher clergy and to seminaries in Italy, they totalled more than half of all Italian libraries in this period. Despite the dispersal of the collections and the suppression of the monasteries themselves in modern times, the surviving monastic libraries remain extraordinarily rich with an invaluable patrimony we must protect, study, promote and hand on to future generations.